Every day, tens of thousands of brute force attacks are launched against servers worldwide, testing the limits of their defences. For those of us new to cybersecurity, these attacks aren’t just statistics: they’re a chance to learn. Setting up a honeypot is an invaluable way to go about this. This post looks at some of the lessons learned from 5 days of honeypot logs.

Honeypots are valuable tools for both experienced security professionals and those, like me, who are new to the field. For seasoned experts, they provide nuanced insights into attacker behaviour and emerging threats, helping refine defensive strategies. For newcomers, honeypots offer a hands-on opportunity to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world application in defensive security.

Setting up and running a honeypot is an incredibly educational experience. It requires configuring servers (whether locally or in the cloud), managing system resources, and actively monitoring logs. These technical tasks build foundational skills essential for anyone aspiring to work in system administration or cybersecurity. The process also introduces tools and configurations used to secure systems against potential threats.

Once operational, a honeypot reveals the types of attacks and interactions that a publicly accessible server might encounter. From observing brute force SSH attempts to analysing post-compromise activity, it serves as a controlled environment to study the tactics, techniques, and procedures attackers employ. This real-world exposure transforms abstract cybersecurity concepts into tangible, actionable insights.

Recently, I decided to deploy a honeypot of my own. I used a Cowrie honeypot hosted on a DigitalOcean droplet, leveraging the opportunity to practice configuring cloud-based services and writing scripts to interpret the logs generated. My goal was to create a detailed report on the collected data. While a separate post discusses the honeypot’s configuration, this post focuses on the insights and analysis derived from the data.

Summary

The honeypot was active for a 5-day period, during which it logged a myriad of different activities and events.

Key metrics from this period include:

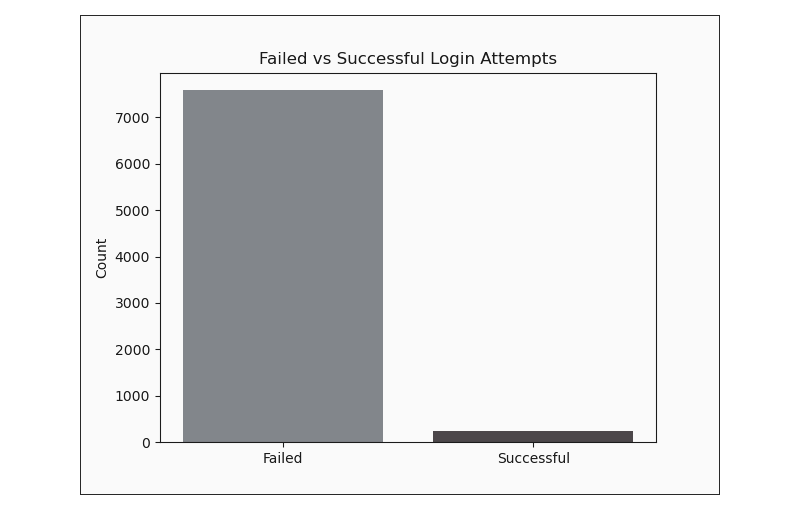

- Successful logins: 233

- Failed logins: 7,586

- Unique IPs: 106

- Total commands executed: 248

- Potential brute force IPs: 30*

* Brute force IPs were identified using a script that flagged IPs exceeding a threshold of 10 login attempts within a 5-minute window. These thresholds were designed to mimic realistic brute force activity and help isolate aggressive attackers.

The 7,586 failed logins during a 5-day period underscore the relentless nature of brute force attacks, often automated and distributed across botnets. Similarly, the 106 unique IPs observed suggest a global distribution of sources, displaying just how broad of an attack surface exposed systems can face.

These figures highlight the volume and variety of interactions a single exposed server can attract. This offers valuable insights into real-world attack patterns.

Username & Password Data

The honeypot was configured to accept 33 distinct username/password combinations, simulating a range of commonly used and default credentials. These included generic combinations like admin:admin123, IoT-specific defaults such as root:vizxv and admin:7ujMko0admin, and even some intentionally weak options like root:password and guest:guest123. This deliberate variety aimed to allow a few, specific username and password combinations as to not simply allow everything in and reduce the quality of results, whilst still mimicking vulnerable systems that attackers frequently target.

Top Username & Password Combinations

This table lists the most frequently attempted username and password combinations observed during the honeypot’s operation. The credentials range from default IoT device logins to common weak passwords, reflecting the tactics attackers often employ in brute force attacks.

| Username | Password | Attempts |

|---|---|---|

| admin | admin | 146 |

| root | 123 | 32 |

| root | root | 51 |

| root | 1 | 30 |

| support | support | 48 |

| root | 12345 | 26 |

| root | admin | 43 |

| pi | raspberry | 25 |

| root | 123456 | 41 |

| system | OkwKcECs8qJP2Z | 41 |

When looking at both succesful and unsuccesful login attempts we can demonstrate the sheer volume of login attempts quite effectively.

The sheer volume of failed login attempts here very effectively communicates the amount of brute force activity experienced while the honeypot was active.

Location Data

While country-based attribution using IP addresses can be misleading, it still offers interesting insights into the geographical distribution of activity. It’s important to remember that geolocation of an IP address does not equate to determining the nationality of an attacker or user. Instead, it simply indicates the registered location of the IP address, which may be influenced by proxies, VPNs, or compromised systems. The following table shows the top 10 countries based on event data in the honeypot.

Events by Country

| Country | Number of Events |

|---|---|

| China | 92 |

| United States | 88 |

| Netherlands | 22 |

| India | 16 |

| Germany | 11 |

| Australia | 10 |

| Hong Kong | 10 |

| Russia | 8 |

| Brazil | 8 |

| Korea | 8 |

Command Execution Data

While the honeypot was active, 248 commands were executed by attackers who were able to successfully log in. Of those commands, these are the top 10:

Top Commands Executed

This table lists the most frequently executed commands, categorised by type and purpose

| Command | Count |

|---|---|

uname -s -v -n -r -m |

97 |

apt |

14 |

sh;shell;su;enable;ping;cd /tmp \|\| cd /var/run \|\| cd /mnt \|\| cd /root \|\| cd /;cd... |

12 |

uname -s -m |

11 |

/ip cloud print |

6 |

uname -a |

6 |

cat /proc/cpuinfo |

6 |

ps \| grep '[Mm]iner' |

6 |

ps -ef \| grep '[Mm]iner' |

6 |

ifconfig |

6 |

This data is perhaps some of the most interesting for me as someone largely new to this field.

Commands such as uname -a and cat /proc/cpuinfo provide attackers with detailed system information, including the OS version, kernel, and CPU architecture. This allows them to tailor subsequent attacks or payloads to the server’s specifications. These sorts of commands can be broadly categorised as reconnaissance and system profiling activity.

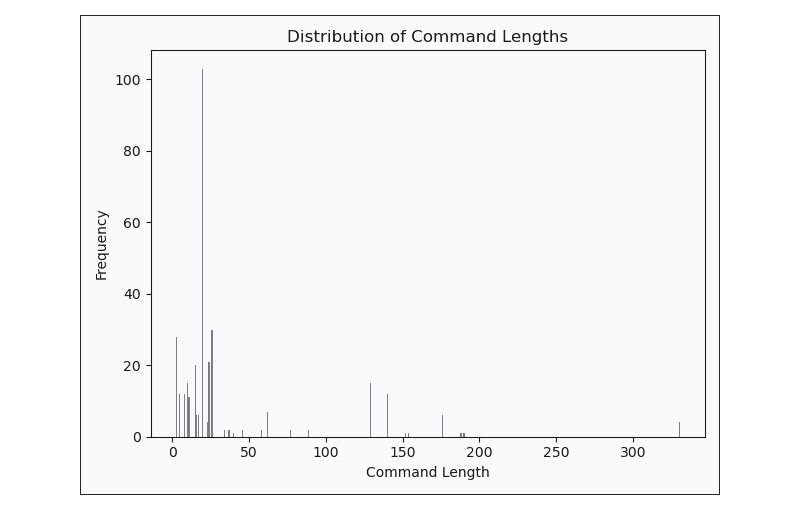

Looking at commands more broadly, we can visualise the length of each command executed to understand the complexity of them, and with that information ascertain whether a majority of the command activity in the honeypot was simple or complex.

While much of the command activity indicated reconnaissance, some proved to be more specific, namely the ps | grep '[Mm]iner' commands. Let’s dig into those examples to find out why.

A Closer Look at Cryptocurrency Miners

One of the more intriguing findings from the honeypot logs involved commands targeting potential cryptocurrency mining processes. Specifically, the attacker issued commands such as ps | grep '[Mm]iner' and ps -ef | grep '[Mm]iner'. These commands are commonly used to check for processes that might indicate active cryptocurrency mining software running on the system.

In this particular case, the attacker connected from the IP address 220.88.51.XXX (geolocated to Korea) and successfully logged in using the credentials root:12345. Once inside, the attacker executed reconnaissance commands like uname -a and cat /proc/cpuinfo, presumably to profile the system and determine its suitability for running mining operations. The repeated use of commands to list and search for active processes, such as ps | grep '[Mm]iner', indicates a specific intent to identify any existing mining activities.

Digging into one particular session, a sequence of events can be established.

Sequence of Events for Attacker IP: 220.88.51.XXX

The attacker’s actions followed a methodical sequence, progressing from brute force login attempts to reconnaissance and miner-related process searches.

1. Connection Established

- Timestamp: 2024-11-21T23:05:12.598438Z

- Event: The attacker initiated an SSH connection to the honeypot on port 22.

2. Login Attempts

- Timestamp Range: 2024-11-21T23:05:13.603693Z to 2024-11-21T23:05:15.916992Z

- Events:

- Failed login with

root:root. - Failed login with

root:admin. - Successful login with

root:12345.

- Failed login with

3. Reconnaissance Commands

Commands Executed:

/ip cloud print- Timestamp: 2024-11-21T23:05:16.258225Z

- Result: Command not found.

ifconfig- Timestamp: 2024-11-21T23:05:16.813545Z

- Result: Displayed network configuration.

uname -a- Timestamp: 2024-11-21T23:05:17.305859Z

- Result: Displayed system profiling information.

cat /proc/cpuinfo- Timestamp: 2024-11-21T23:05:17.835328Z

- Result: Displayed CPU details.

4. Miner Process Reconnaissance

Commands Executed:

ps | grep '[Mm]iner'- Timestamp: 2024-11-21T23:05:18.365422Z

- Result: Searched for active miner-related processes.

ps -ef | grep '[Mm]iner'- Timestamp: 2024-11-21T23:05:18.898667Z

- Result: Performed an extended search for miner-related processes.

5. File and Configuration Reconnaissance

- Command:

ls -la /dev/ttyGSM* /dev/ttyUSB-mod* /var/spool/sms/* /var/log/smsd.log /etc/smsd.conf* /usr/bin/qmuxd /var/qmux_connect_socket /etc/config/simman /dev/modem* /var/config/sms/*- Timestamp: 2024-11-21T23:05:19.438810Z

- Result: Searched for GSM, SMS, and modem-related files.

6. Miscellaneous Command

- Command:

echo Hi | cat -n- Timestamp: 2024-11-21T23:05:19.967828Z

- Result: Displayed “Hi” with line numbers (likely a test or error).

7. Session Closed

- Timestamp: 2024-11-21T23:06:07.361658Z

- Event: The connection was closed after 54 seconds of activity.

This sequence of events allows us to paint a picture of the attackers activity within the honeypot from their initial connection to the honeypot until the session was closed. Based on this timeline of events, we’re able to put together a fairly comprehensive list of Indicators of Compromise (IOCs):

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

- IP Address:

- Malicious Source IP:

220.88.51.XXX - Context: Initiated an SSH session and performed reconnaissance. While this IP was observed engaging in malicious behaviour, it may represent a compromised system rather than the attacker’s true origin.

- Malicious Source IP:

- Username/Password Pairs:

root:12345(successfully exploited)

- Commands Executed:

- Reconnaissance:

-

uname -a-cat /proc/cpuinfo-ifconfig - Process Searching:

-

ps | grep '[Mm]iner'-ps -ef | grep '[Mm]iner' - File Enumeration:

-

ls -la /dev/ttyGSM* ...(attempting to locate modem or SMS-related configurations)

- Reconnaissance:

-

- SSH Client Details:

- Version:

SSH-2.0-libssh2_1.11.0

- Version:

These Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) can be integrated into SIEM tools to enhance detection capabilities or shared with threat intelligence networks to bolster community defences. For instance, monitoring for commands like ps | grep '[Mm]iner' could help detect crypto miner-related activity across other systems.

Wrapping Up

Honeypots like Cowrie provide a valuable opportunity to understand the behaviours and techniques employed by attackers. Through this exercise, I gained valuable insights into the reconnaissance and targeting strategies commonly used in real-world attacks. From brute force login attempts to process and configuration searches, the data collected from the honeypot highlights the persistent and methodical nature of modern cyber threats.

For newcomers like me, deploying a honeypot is more than just an educational endeavour, it’s a practical step toward understanding the dynamics of defensive security. The process of configuring, monitoring, and analysing a honeypot builds the skills necessary to proactively defend systems.

The data presented in this post is a small piece of the larger puzzle, not only in understanding the data logged by this honeypot specifically, but the cyber landscape as a whole. By sharing these findings, including the Indicators of Compromise and detection techniques, I hope to contribute to the broader conversation about improving security practices. Whether you’re a seasoned professional or just starting out, honeypots are a powerful tool for turning theoretical knowledge into actionable insights.

As I continue to explore defensive security, I plan to build on these findings, refining my detection techniques and sharing new discoveries. If you’re considering setting up your own honeypot, I encourage you to do so: it’s a hands-on experience that will expand your understanding of both offensive and defensive strategies in cybersecurity.